tinygrad-notes

JIT in tinygrad

Latest commit id when I wrote this was f2bee341970f718298d020d7b38cb33239c67b73, if you want to follow the examples.

Compiling code for GPU device has two steps, 1. compile the kernel source code into byte code, 2. convert the byte code into

GPU executable. The first step is always cached and reused in Tinygrad. The second step, however,

requires explicit usage of TinyJit, which is what we are mainly focusing on when talking about JIT.

Compiling kernel code

When we compute a tensor, some GPU code must be rendered. For example, a 4 by 4 matrix elementwise addition might render this CUDA code:

extern "C" __global__ void __launch_bounds__(1) E_16(float* data0, float* data1, float* data2) {

int gidx0 = blockIdx.x; /* 16 */

float val0 = *(data1+gidx0);

float val1 = *(data2+gidx0);

*(data0+gidx0) = (val0+val1);

}

This render process is covered in the intro and pattern matcher post, and it comes directly from the UOp. A kernel source code originates from the Tensor whose “realize” methods are being called, upon which a UOp tree is generated, lowered, and finally rendered into such string. Afterwards, the rendered source code is compiled into byte code:

class CUDACompiler(Compiler):

def _compile_program(self, src:str, nvrtc_get_content:Callable, nvrtc_get_size:Callable) -> bytes:

nvrtc_check(nvrtc.nvrtcCreateProgram(ctypes.byref(prog := nvrtc.nvrtcProgram()), src.encode(), "<null>".encode(), 0, None, None))

nvrtc_check(nvrtc.nvrtcCompileProgram(prog, len(self.compile_options), to_char_p_p([o.encode() for o in self.compile_options])), prog)

data = _get_bytes(prog, nvrtc_get_content, nvrtc_get_size, nvrtc_check)

nvrtc_check(nvrtc.nvrtcDestroyProgram(ctypes.byref(prog)))

return data

We do something similar on Metal:

class MetalCompiler(Compiler):

def compile(self, src:str) -> bytes:

#...

src_padded, params_padded = src.encode() + b'\x00'*(round_up(len(src) + 1, 4) - len(src)), params.encode() + b'\x00'

request = struct.pack('<QQ', len(src_padded), len(params_padded)) + src_padded + params_padded

#...

return ret

See how we are passing src: str which is the rendered source code to _compile_program or compile, and then calling some deeper

APIs like nvrtc? You can also read up on the runtime compilation library documentation for CUDA,

Apple’s runtime compilation is not documented, but you can read up on the

PR that integrated it.

This compilation could take some time. So we want to cache and re-use it. If we see the same UOp on the same GPU device,

we can be sure that compilation will return the same blob, and that’s the caching strategy. You can see this in the

implementation of get_runner:

method_cache: dict[tuple[str, bytes, int, int, bool], CompiledRunner] = {}

def get_runner(device:str, ast:UOp) -> CompiledRunner:

ckey = (device, ast.key, BEAM.value, NOOPT.value, False)

if cret:=method_cache.get(ckey): return cret

bkey = (device.split(":")[0], ast.key, BEAM.value, NOOPT.value, True)

if bret:=method_cache.get(bkey):

method_cache[ckey] = ret = CompiledRunner(replace(bret.p, device=device), bret.lib)

else:

prg: ProgramSpec = get_kernel(Device[device].renderer, ast).to_program()

method_cache[ckey] = method_cache[bkey] = ret = CompiledRunner(replace(prg, device=device))

return ret

This function converts a UOp into runnable program. See to_program()? That’s where rendering and compilation

takes place. If we come across this UOp a second time, we can skip the compilation and re-use the blob (.lib).

However, the byte code isn’t something we can execute directly, unlike regular C++ code compiled with CLANG or GCC. The GPU device requires a second stage of compilation, to make them actually executable.

Compiling GPU command

When we want to execute things on the GPU, we have to call a set of different API to make the compiled bytecode executable. On top of that we also specify some other options such as launch dimensions, buffer sizes etc. The GPU executable is called a compute graph, or compute pipeline.

In fact, this is a somewhat universal conceptual model adopted by all the major GPU platforms.

On Apple it’s called a

pipeline state object.

On WebGPU it’s called a compute pipeline.

On CUDA, it’s just called a graph.

Although on cuda it may seem less obvious if you are using the triple angle bracket calling form:

(e.g. add_vectors<<< blk_in_grid, thr_per_blk >>>(d_A, d_B, d_C);), but under the hood it just calls the same APIs for you.

Initializing the compute graph is similar to compiling source code, and could take some time, but it is re-useable. Each GPU platform also provide instructions on how to re-use them. See this for CUDA, and the actual API we call. On Apple, this is referred to as “IndirectCommandEncoding”, see its usage here. On WebGPU, it is called GPURenderBundleEncoder

Reusing the compute graph is what TinyJit does!

When a tensor is realized, a set of GPU commands are created. A function wrapped with TinyJit will record those

commands, and start capturing them if it sees it more than once. The capture process follows the target platform’s

API. The next time this function is run, only the captured graph is being executed. See this simplified code:

class TinyJit():

def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs) -> ReturnType:

input_buffers, var_vals, names, st_vars_dtype_device = _prepare_jit_inputs(args, kwargs)

if not JIT or self.cnt == 0:

ret = self.fxn(*args, **kwargs)

elif self.cnt == 1:

ret = self.fxn(*args, **kwargs)

self.captured = CapturedJit(ret, jit_cache, input_replace, extra_view_inputs, names, st_vars_dtype_device)

elif self.cnt >= 2:

ret = self.captured(input_buffers, var_vals)

self.cnt += 1

return ret

Usage

Let’s suppose we are running some forward pass in a loop. Each iteration we get a different input, and it’s multiplied elementwise with some weight, and the result is summed:

from tinygrad import Tensor, TinyJit

import time

weight = Tensor.empty(4, 4)

def forward(x: Tensor):

c = (x * weight).contiguous()

c.sum(0).realize()

for i in range(4):

start = time.time()

x = Tensor.empty(4, 4)

forward(x)

end = time.time()

print(f"Iteration {i} took {(end - start)*1000:.2f}ms")

I am using .empty here to minimize the DEBUG output we will see, and calling .contiguous to prevent the multiply

and sum from being fused into one kernel (TinyJit will only batch when there are more than 1 kernel, to justify

the overhead). I am also recording the time to show the speedup.

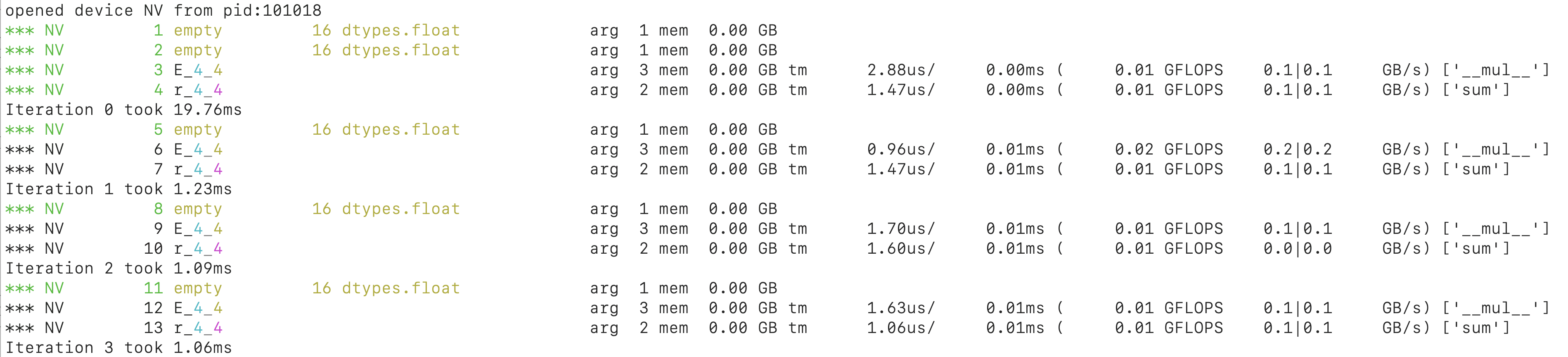

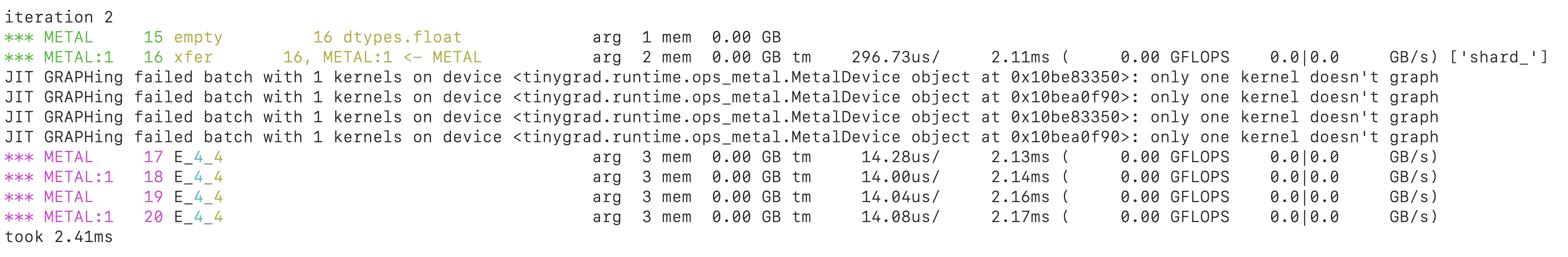

If we run this script with DEBUG=2 python script.py:

You see that in each iteration, we are executing two kernels. Recall that running code on the GPU is a two step process, first compile source code to byte code, then create a compute graph/pipeline (i.e. compile bytecode to GPU machine code). Here we are re-using the first compilation result, but the second step is repeated everytime a kernel runs. Looking at the speed, the first iteration takes longest, as expected, because it is compiling source code, and also creating the compute graph/pipeline. Starting from the second iteration, there’s significant speed up already. However, it remains at ~1ms from there on, mostly because they are repeating the same compute graph/pipeline creation.

Let’s apply TinyJit:

@TinyJit

def forward(x: Tensor):

#...

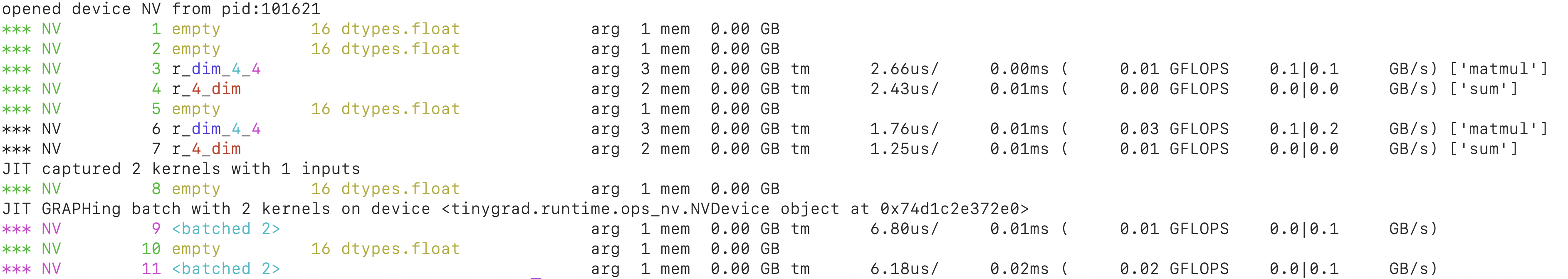

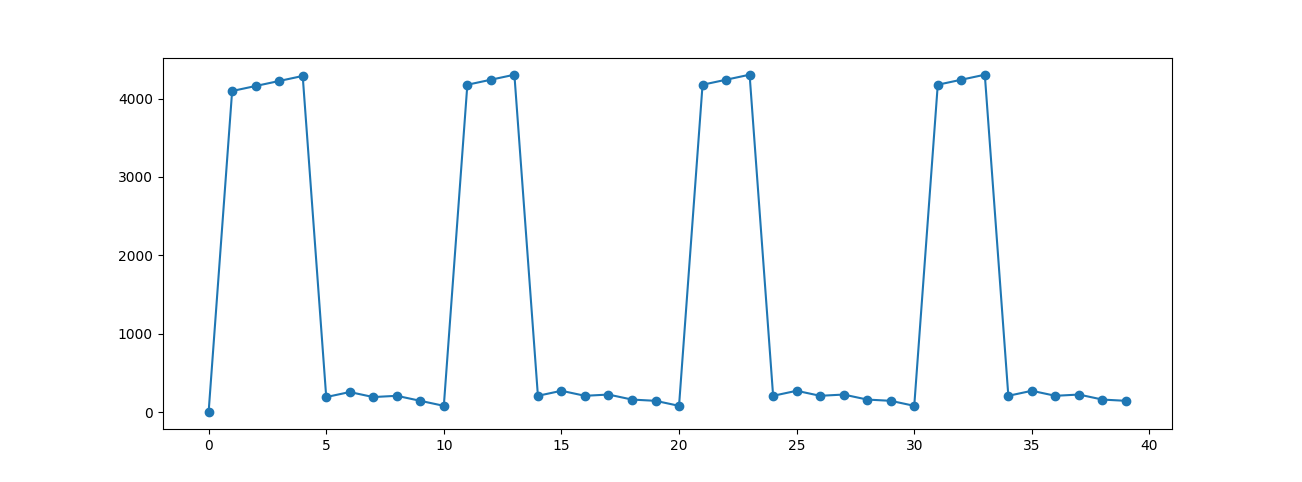

We see that the two kernels, upon the second run and third run are now batched, the number in <batched 2> indicate

how many kernels were actually batched together. This batching merged the two kernels into a single, reuseable compute

graph/pipeline, and significantly improved the speed!

You can verify it by looking at the speed JIT capturing starts on iteration 1, then on iteration 2 the captured items are converted into re-useable graphs. These all came with some overhead, so we did not see much speed up. But on iteration 3, the compute graph are executed directly, and it’s taking only 0.39 ms!

Tricks and caveats

There are some tricks and caveats to using JIT.

Non GPU statements

For example, any non-GPU statements will be skipped, the print statement here will be gone after 2 iterations:

@TinyJit

def forward(x: Tensor):

c = (x * weight).contiguous()

print(f"shape of c {c.shape}")

c.sum(0).realize()

Shape alignment

Reusing the compute graph (hence TinyJit) requires the buffers to be of the same size. This is more of an API

restriction rather than Tinygrad’s limitation. In TinyJit, this is enforced by checking the equality of shapetracker.

In the above example, weight is constant, so it will always be valid. x can potentially change, we must be make

sure that its shapetracker has the same shape, strides offset and mask across all the iterations. For example,

you may have an input tensor that’s growing over iterations, a common pattern in decoder, but this will fail:

@TinyJit

def forward(x: Tensor):

return weight.matmul(x).contiguous().sum().realize()

for i in range(4):

x = Tensor.empty(4, i+1)

forward(x)

The trick is to allocate the largest sized buffer required, and use a subset of it when iterating. To do that, we use a symbolic variable for the shape, and on each iteration, bind the required value to it:

for i in range(4):

dim = UOp.variable("dim", 1, 4).bind(i+1)

x = Tensor.empty(4, dim)

forward(x)

It will then happily batch:

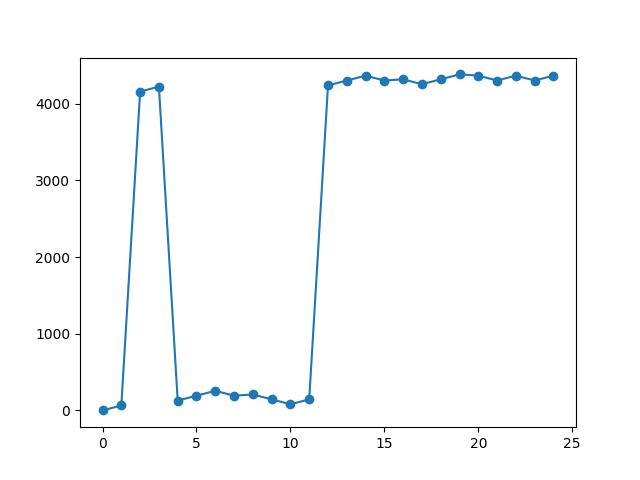

You can see that on each iteration, we are creating a buffer with 16 elements, even though x is only of size 16 on

the last iteration. This is just one of those compromises.

Nested JIT

You may have seen models that already have a forward method wrapped in TinyJit, but then you want to also jit the loss function:

@TinyJit

def forward(x: Tensor):

c = (x * weight).contiguous()

print(c.shape)

return c.sum(0).realize()

@TinyJit

def train_step(i):

print('iteration', i)

x = Tensor.empty(4, 4)

logits = forward(x)

loss = logits.reshape((4, 1)).expand((4, 4)).contiguous().sum(1)

loss.realize()

for i in range(5):

train_step(i)

This will give you an error because you can’t nest JIT:

RuntimeError: having TinyJit inside another TinyJit is not supported len(capturing)=1 capturing=[<tinygrad.engine.jit.TinyJit object at 0x7e1fff663df0>]

That’s why you often see there are two versions of forward, one with Jit and the other without, for example, in the llama transformer:

class Transformer:

def __init__(self, dim:int, hidden_dim:int, n_heads:int, n_layers:int, norm_eps:float, vocab_size, linear=nn.Linear, n_kv_heads=None, rope_theta=10000, max_context=1024, jit=True, feed_forward=FeedForward):

#...

self.forward_jit = TinyJit(self.forward) if jit else None

def forward(self, tokens:Tensor, start_pos:Union[Variable,int], temperature:float, top_k:int, top_p:float, alpha_f:float, alpha_p:float):

#...

return sample(logits.flatten(), temperature, top_k, top_p, alpha_f, alpha_p).realize()

def __call__(self, tokens:Tensor, start_pos:int, temperature:float=0.0, top_k:int=0, top_p:float=0.8, alpha_f:float=0.0, alpha_p:float=0.0):

if tokens.shape[0:2] == (1,1) and self.forward_jit is not None and start_pos != 0:

return self.forward_jit(tokens, Variable("start_pos", 1, self.max_context).bind(start_pos), temperature, top_k, top_p, alpha_f, alpha_p)

return self.forward(tokens, start_pos, temperature, top_k, top_p, alpha_f, alpha_p)

And in the MNIST example, the model itself isn’t decorated with JIT, but rather, the training loop handles it:

class Model:

def __init__(self):

self.layers: List[Callable[[Tensor], Tensor]] = [

nn.Conv2d(1, 32, 5), Tensor.relu,

#...

lambda x: x.flatten(1), nn.Linear(576, 10)]

def __call__(self, x:Tensor) -> Tensor: return x.sequential(self.layers)

@TinyJit

@Tensor.train()

def train_step() -> Tensor:

samples = Tensor.randint(getenv("BS", 512), high=X_train.shape[0])

loss = model(X_train[samples]).sparse_categorical_crossentropy(Y_train[samples]).backward()

opt.step()

return loss

graph vs simple reuse

One detail I glossed over is that JIT can operate in either batched graph mode, or simple re-use mode. Batched graph mode is what I have

been describing so far, but one important note is the fact it is batch multiple kernels into one.

Sometimes the kernels that follow one another may not be able to be batched, and as a result, TinyJit will just

re-use the previously created CompiledRunner, not taking advantage of the graph capability.

Here I give a contrived example, it illustrates the reason why kernels aren’t batched/graphed, but in a future version of tinygrad, it might be improved such that they get batched properly. In multi gpu training, we often have two tensors sharded on two devices doing identical work, this result in the same kernel being dispatched on each device. If the order is interleaved, then JIT won’t be able to batch them:

from tinygrad import Tensor, TinyJit, UOp

import time

import tinygrad.nn as nn

from tinygrad.device import Device

shards = [f"{Device.DEFAULT}", f"{Device.DEFAULT}:1"]

weight = Tensor.empty(4, 4).shard_(shards)

@TinyJit

def forward(x: Tensor):

return x.mul(weight).contiguous().mul(weight)

for i in range(4):

print(f"\niteration {i}")

s = time.time()

x = Tensor.empty(4, 4).shard_(shards).realize()

ret = forward(x).realize()

e = time.time()

print(f"took {(e-s)*1000:.2f}ms")

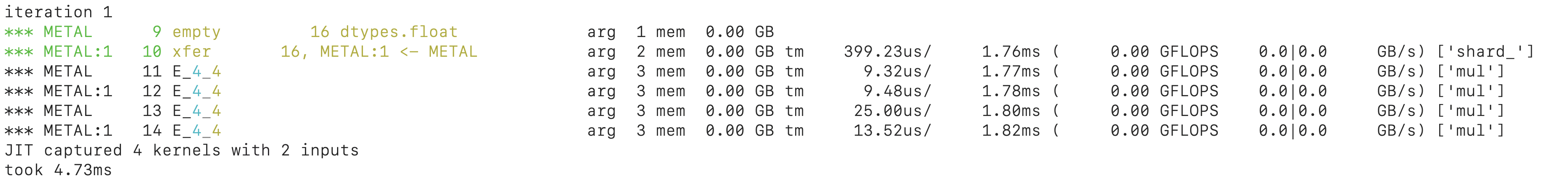

The regular run shows that we have six compute kernels:

The first two were the initialization for x. 16 elements were allocated on device 0, and we copy them to the second device with “XFER”. Then the same multiplication were done on each device, and we see that JIT captured all four. However, in the next run, we see that the batching failed:

The reason is that JIT batching is handled sequentially. One of the criteria is looking at whether the current kernel is on the same device as the previous one:

# Snippet from jit implementation

for ji in jit_cache: # Iterate through each kernel

if isinstance(ji.prg, CompiledRunner): ji_graph_dev = ji.prg.dev

# Check if this device is the same as previous one

can_share_graph = (ji_graph_dev == current_device or (isinstance(graph_class, type) and issubclass(graph_class, MultiGraphRunner)) and

type(ji_graph_dev) is type(current_device))

current_device = ji_graph_dev

Because the scheduling has interleaved the kernel for two devices, this mechanism failed to recognize the continuity. And as a result, each time TinyJit tries to batch, it sees just one kernel, and refuses to do that, hence the error message. Remember that graphing/batching have their own overhead and is only justified when you have many kernels.

TinyJit now will just execute those kernels as is, only re-using the CompiledRunner from previous compilation and will

call the GPU API that recompile them into the device. This is indicated by the magenta color for the kernels in the output.

Memory management

TinyJit holds on to all the buffers throughout its life time, this means the memory usage will remain at the max amount needed for a function call. This may cause issues if your function requires memory release in the middle.

For example, if you have an intermediate buffer to hold some data, and is later released:

weight = Tensor.empty(4, 4)

def forward(x: Tensor):

x2 = Tensor.empty(32, 32).contiguous().realize()

x = (x + x2[:4, :4]).contiguous()

return x.mul(weight).contiguous().sum(0)

for i in range(4):

x = Tensor.empty(4, 4)

ret = forward(x).realize()

Note that I have added .contiguous() and realize() just to prevent certain optimization, in order to show this

contrived example. It may look weird, but it is one of multi GPU examples, where you have shuffle data between

devices. During the process, an intermediate buffer is allocated to hold the temporary data, and then released. It

is similar to using a temporary variable when swapping two variables:

temp = a

a = b

b = temp

When dealing with large buffers, this temporary variable (x2) would ideally be released as soon as it has done the job.

With some custom memory tracking code, we can see that this is the case without JIT applied:

However, if you were to apply jit:

@TinyJit

def forward(x: Tensor):

x2 = Tensor.empty(32, 32).contiguous().realize()

x = (x + x2[:4, :4]).contiguous()

return x.mul(weight).contiguous().sum(0)

Now the entire temporary buffer is retained throughout. Just something to be cautious about.

JIT does buffer reuse

Again this may be something that gets improved in future version of tinygrad. The input and output of a JIT’ted function

is re-used, this may lead to surprising behaviour if you are using the output buffer as if they were unique instance.

In other words, if you are using a concatenate function to accumulate all the output from a JIT, then you may see the

content is swapped:

from tinygrad import Tensor, TinyJit

import math

@TinyJit

def replace_if_zero(tokens: Tensor):

tokens = (tokens == 0).where(-math.inf, tokens).contiguous()

_ = (tokens == 0).all()

return tokens, _

ctx = Tensor([

[0, 0]

])

_a = [

[1, 7],

[2, 0],

[3, 2],

[4, 0],

]

for i in range(0, len(_a)):

a = Tensor(_a[i]).reshape((1, -1))

a, _ = replace_if_zero(a)

ctx = ctx.cat(a, dim=0)

print(ctx.numpy())

This is a processing step for an LLM decoder, a common filter technique to remove unwanted tokens. In this example,

if the tokens contain zero, we replace its value to negative infinite. You can imagine the zero being a keyword we don’t

want, maybe it’s a sensitive token, maybe it’s a foreign word when you only want to output English tokens.

Nevertheless, we start of with a ctx tensor that contains a starting sequence. In each iteration of the loop, we

create a tensor that contain a row from _a, this is analogous to getting output from a decoder model. Then we check

if the content has any zeros and replace it with negative infinite by tokens = (tokens == 0).where(-math.inf, tokens)

and we append this output to the ctx tensor by doing a concatenation. There’s an additional .all being returned.

Practically this is used to check if it’s all zeros, in which case we might want to terminate the generation. It

serves another purpose here for the demo, JIT requires at least two kernels to graph.

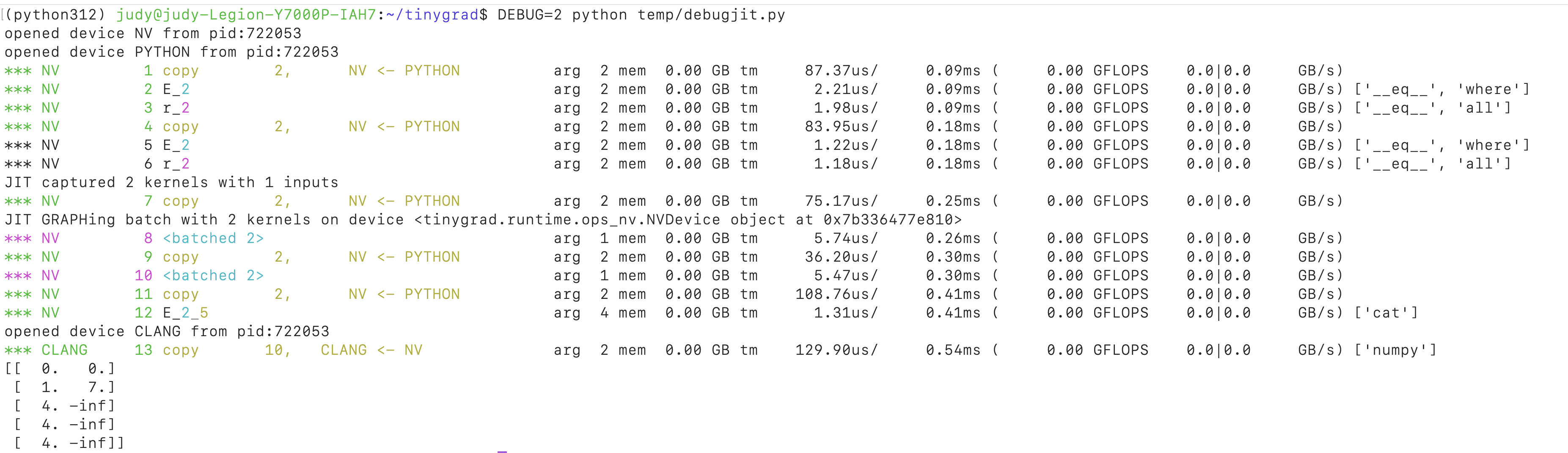

Turning on DEBUG=2 you can see the

replace function is JIT’ted:

But the result may not be what you were expecting:

[[ 0. 0.]

[ 1. 7.]

[ 4. -inf]

[ 4. -inf]

[ 4. -inf]]

If you remove TinyJit decorator, you see we get the result:

[[ 0. 0.]

[ 1. 7.]

[ 2. -inf]

[ 3. 2.]

[ 4. -inf]]

Alternatively, if you add a call to ctx at the end of the loop, we also get the same result:

for i in range(0, len(_a)):

a = Tensor(_a[i]).reshape((1, -1))

a, _ = replace_if_zero(a)

ctx = ctx.cat(a, dim=0)

ctx.realize()

Why’s that? TinyJit reuses the buffer, but cat is a lazy operation. When we are concatenating three tensors, what

cat does is pad each with the required amount, and then add together. For example, if you are catting three

rows, then the first row will be expanded into three rows, with the last two rows being zeros. Second tensor

will have the first and last row having zeros, and so on. But because TinyJit is re-using the buffers, you are

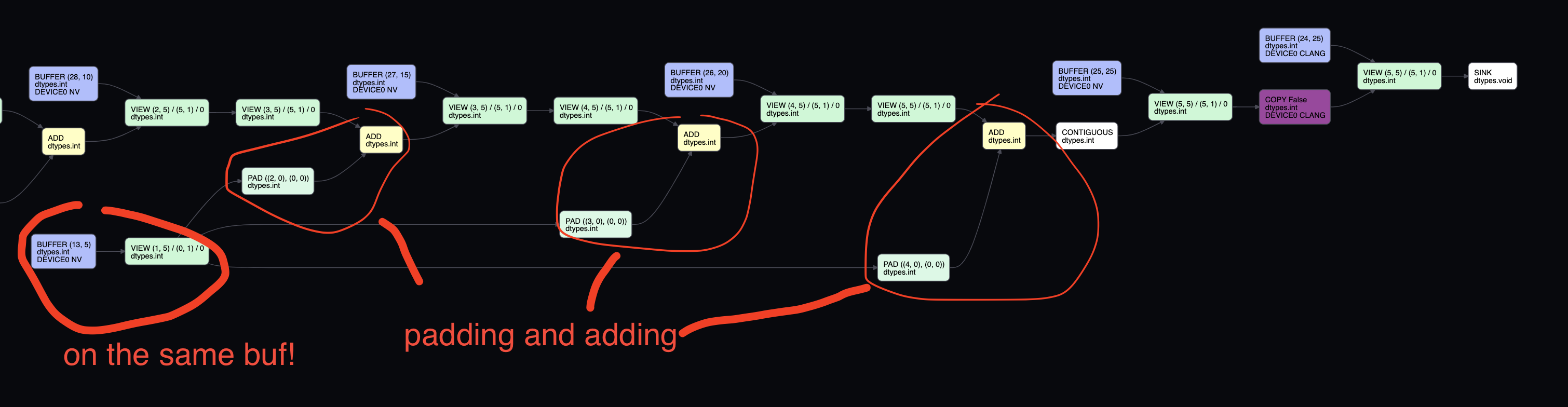

essentially just adding the same tensor thrice. Let’s use VIZ=1 flag to see this

(check my other post on this tool):