tinygrad-notes

How to profile a run

After getting tinygrad, you can start experimenting with the examples folder, it would be good to be able to understand how well the GPU is being utilized and where to find room for optimization, that’s where profiling comes to play. For me, the motivation is to figure out whether my intel macbook’s performance has been maxed out, or is it underutilized because people don’t care much about this old piece of metal?

We use the MNIST image recognition training example:

PYTHONPATH='.' python examples/beautiful_mnist.py

This will perform a training and show you a progress bar. On my computer, the training is slow. Setting DEBUG=2 allow you to see the kernels being dispatched to GPU and the relevant info on it.

*** EXT 1 synchronize arg 1 mem 0.22 GB tm 0.81us/ 0.00ms ( 0.00 GFLOPS, 0.00 GB/s)

*** METAL 2 copy 4, METAL <- EXT arg 2 mem 0.22 GB tm 72.80us/ 0.07ms ( 0.00 GFLOPS, 0.00 GB/s)

*** EXT 3 synchronize arg 1 mem 0.22 GB tm 0.60us/ 0.07ms ( 0.00 GFLOPS, 0.00 GB/s)

*** METAL 4 copy 4, METAL <- EXT arg 2 mem 0.22 GB tm 39.48us/ 0.11ms ( 0.00 GFLOPS, 0.00 GB/s)

*** EXT 5 synchronize arg 1 mem 0.22 GB tm 0.67us/ 0.11ms ( 0.00 GFLOPS, 0.00 GB/s)

*** METAL 6 copy 4, METAL <- EXT arg 2 mem 0.22 GB tm 42.56us/ 0.16ms ( 0.00 GFLOPS, 0.00 GB/s)

0%| | 0/70 [00:00<?, ?it/s]

The information might seem overwhelming, so I will again resort to the old dot product example

from tinygrad.tensor import Tensor

a = Tensor([1,2])

b = Tensor([3,4])

res = a.dot(b).numpy()

print(res) # 11

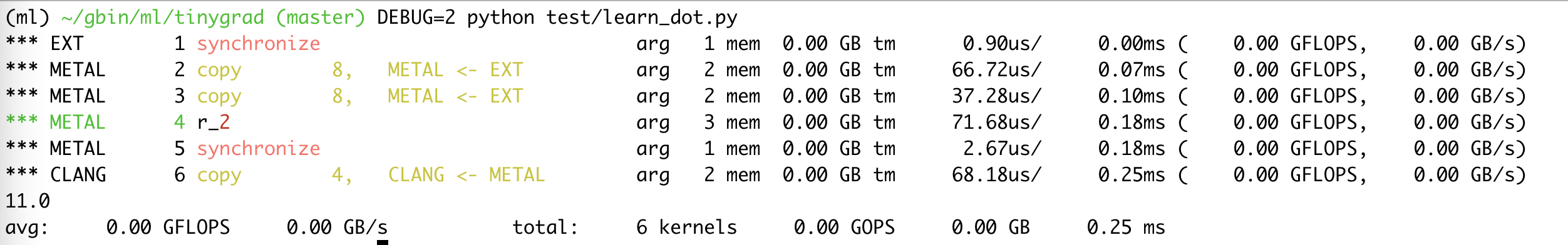

The output is:

If you set DEBUG to 5, you will see that our ScheduleItem are expanded with the uops and kernel code. Those haven’t changed. We focus on what wasn’t covered before, the stats of each operation. For a dot product operation, we have six operations being scheduled. The first is obtaining an acknolwedgement from numpy (EXT), represented by “Synchronize”. Second is copy the data from numpy (EXT) to GPU (METAL). Third is the same. These two copy put our [1,2] and [3,4] to GPU memory. The third is our kernel code that compute the dot product. Fourth is an acknolwedgement from the GPU, signaling that the device that depends on GPU can now resume (see commmand queue tutorial). The sixth is a copy op from GPU to CPU such that we can print the result 11. The goal is to quantify how long and how much resource each step takes.

Let me breakdown the output to you:

For the first op:

*** EXT 1 synchronize

We obtain the following stats:

arg 1: It has 1 buffer passed to it.

mem 0.00 GB: Memory usage is 0.00 GB.

tm 0.86us/ 0.00ms: tm is short for time measured. 0.86us means

this operation took 0.86 microseconds. 0.00 means the total global time since

the program started has elapsed 0.00 milliseconds. It’s not actually zero because

the precision is only 2 decimals. But after a few op we will see it starting to

accumulate.

( 0.00 GFLOPS, 0.00 GB/s): this summarizes the total number of flops for

this specific operation and the speed in which data are being moved.

The second one will now seem more obvious:

*** METAL 2 copy 8, METAL <- EXT arg 2 mem 0.00 GB tm 74.44us/ 0.08ms ( 0.00 GFLOPS, 0.00 GB/s)

It reads: the second operation runs on Metal, and is a copy op. This op has a size of 8 bytes (recall we are copying two int32 numbers, so a 32bit int is 4 bytes, two is 8 bytes). The op also copies from EXT to METAL. It has two buffers (one on the EXT and the other on METAL). The memory usage is 0.00GB (precision shadowed the actual value). Time elapsed since the program started is 0.08 milliseconds and the time it took for this op is 74.44 microseconds.

Next part is the FLOPS and GB/s part.

In a typical GPU, we have memory units and processing units. Between them sits a memory interface. This interface passes data around and have two properties that describe its capability: memory speed and memory bandwidth.

interface

--------->

processing unit ---------> memory

--------->

In this imaginary GPU, we have a single processing unit and a single memory unit connected by a memory interface that’s 3 bit wide (i.e. there are three lanes). Suppose each lane can pass data at 8 bits per second, then we say the Memory speed is 8bps. Since there are three lanes in total, the total throughput within a second is 8bits * 3 = 24bps, which is termed memory bandwidth.

I have a Radeon Pro 5500M on my laptop, which offers 4GB of VRAM, 192GB/s memory bandwidth, 12Gbps memory speed, 4.0 FP32 TFLOPS, 1300MHz engine clocks, which is quite slow, but let me still break down the specs.

The memory speed 12Gbps reads 12 gigabits per second, and the total throughput memory bandwidht is 192 giga bytes per second (GB/s), recall that 1 byte is 8 bits, we can do a math to find out that the total number of memory lanes is 192 * 8 / 12 = 128, which is called Memory Interface Width. The unit is denoted in bits, so this GPU’s has 128 bits memory interface width. And the total amount of memory avaialble is 4GB.

The clock rate (Engine clocks) is 1300MHz, meaning the processing unit operates at 1300 mega hertz, which translates to 1.3 billion cycle per second. Cycle here refers to the instruction cycle in processor, feel free to search up on relevant info.

And the 4.0 FP32 TFLOPS refers to how fast it can do floating point 32 arithmetic. This is more commonly found in ML article. If you recall our dot product example (1 * 3 + 2 * 4 = 11), we are multiplying 2 floating point numbers and adding them together. Each floating point number is represented by 32 bits, and we did two multiplication and 1 addition. So the total FLOPS we did in a dot product operation is 3 FLOPS. If this whole thing takes 1 second in a GPU, then it has a 1.0 FP32 FLOPS performance. What can my GPU do? 4 teraflops per second, which is 4 trillion flops. I think in theory you would calculate the total number of flops for your model during training or inference, and figure out a theoritcal upper limits for the processing time. Do note that this doesn’t consider data movement which also takes time.

Now if we make the MNIST run with DEBUG=2 for longer, we can see where things take up time and also the amount of FLOPS, memory movement that occur at each expensive kernels.