tinygrad-notes

Explaining the symbolic mean bounty

You can check out commit f3de17912f45cf7e45aa2004a0087346fd5fc54a to experiment with how things are before the implementation.

The bounty is to add support for calculating the mean of a tensor (across a certain dimension) using symbolic variable. To understand what that means, let’s look at a relevant example. The scrip below sums up a tensor:

from tinygrad import Tensor

a = Tensor.rand(4)

b = a.sum()

print(b.numpy())

We can run this with DEBUG=5 python script.py and see the generated kernel

code:

#include <metal_stdlib>

using namespace metal;

kernel void r_4(device int* data0, const device int* data1, uint3 gid [[threadgroup_position_in_grid]], uint3 lid [[thread_position_in_threadgroup]]) {

int acc0 = 0;

int val0 = *(data1+0);

int val1 = *(data1+1);

int val2 = *(data1+2);

int val3 = *(data1+3);

*(data0+0) = (val3+val2+val1+val0+acc0);

}

There’s nothing too interesting here, but suppose now we are doing the sum operation on two different tensors:

from tinygrad import Tensor

a = Tensor.rand(4)

b = a.sum()

print(b.numpy())

c = Tensor.rand(8)

d = c.sum()

print(d.numpy())

You will now see a second kernel, in addition to the one from earlier:

#include <metal_stdlib>

using namespace metal;

kernel void r_8(device int* data0, const device int* data1, uint3 gid [[threadgroup_position_in_grid]], uint3 lid [[thread_position_in_threadgroup]]) {

int acc0 = 0;

int val0 = *(data1+0);

int val1 = *(data1+1);

int val2 = *(data1+2);

int val3 = *(data1+3);

int val4 = *(data1+4);

int val5 = *(data1+5);

int val6 = *(data1+6);

int val7 = *(data1+7);

*(data0+0) = (val7+val6+val5+val4+val3+val2+val1+val0+acc0);

}

The downside of having two kernels is that the compilation has to be done twice, once for each kernel. Although we can already tell that the two tensors are quite similar, and in theory, we should have some way of reusing the same compilation result for both tensors’s sum operation. That’s where symbolic comes to play. We can initialize a tensor with a symbolic shape, and bind the value to it, such that the compilation has to be done only once and cached:

from tinygrad import Tensor

from tinygrad.shape.symbolic import Variable

length = Variable('length', 4, 8)

length = length.bind(4)

a = Tensor.rand(length)

b = a.sum()

print(b.numpy())

length, _ = length.unbind()

length.bind(8)

c = Tensor.rand(length)

d = c.sum()

print(d.numpy())

A little bit of explanation might help. length is a special object

of type Variable, it serves as a placeholder for a range of values, in which

case we put 4 and 8, meaning it can represent numbers 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8. When

we create a tensor of shape length, we have to assign a value to it, such that

the sum can get concrete values for the operation. After that, when we want to

assign a different value, we have to unbind it first, then re-bind, in which

case we assign value 8 and used it to create a tensor of length 8.

If you run the script again, you should see just one kernel, instead of two:

#include <metal_stdlib>

using namespace metal;

kernel void r_3Clength5B42D85D3E(device float* data0, const device float* data1, constant int& length, uint3 gid [[threadgroup_position_in_grid]], uint3 lid [[thread_position_in_threadgroup]]) {

float acc0 = 0.0f;

for (int ridx0 = 0; ridx0 < length; ridx0++) {

float val0 = *(data1+ridx0);

acc0 = (val0+acc0);

}

*(data0+0) = acc0;

}

There are two things interesting here. First, there’s only one kernel, meaning we only did the compilation once, cached it and re-used it when we sum the second tensor. Second, the kernel itself can serve tensors that has different lengths, which allows us to use just one kernel.

The way this kernel works is by having an additional parameter: constant int& length

whose value is passed in when this kernel is dispatched. You see that in the loop,

it uses ridx0 < length to bound the iteration, which allows it to work for any

length. Normally, when we dispatch a kernel, we are passing the data pointer for

its input buffer, but here you can see that we can also pass in the special

value for the tensor’s length. Things become clearer if you look at the IR Uops

that was generated:

0 UOps.DEFINE_GLOBAL : ptr.dtypes.float [] (0, 'data0', True)

1 UOps.DEFINE_GLOBAL : ptr.dtypes.float [] (1, 'data1', False)

2 UOps.DEFINE_VAR : dtypes.int [] <length[4-8]>

3 UOps.DEFINE_ACC : dtypes.float [] 0.0

4 UOps.CONST : dtypes.int [] 0

5 UOps.LOOP : dtypes.int [4, 2] None

6 UOps.LOAD : dtypes.float [1, 5] None

7 UOps.ALU : dtypes.float [6, 3] BinaryOps.ADD

8 UOps.PHI : dtypes.float [3, 7, 5] None

9 UOps.ENDLOOP : [5] None

10 UOps.STORE : [0, 4, 8] None

We have a DEFINE_VAR and the LOOP op uses it as the input, that’s how

symbolic variable works in action. The actual implementaion is in this

older PR.

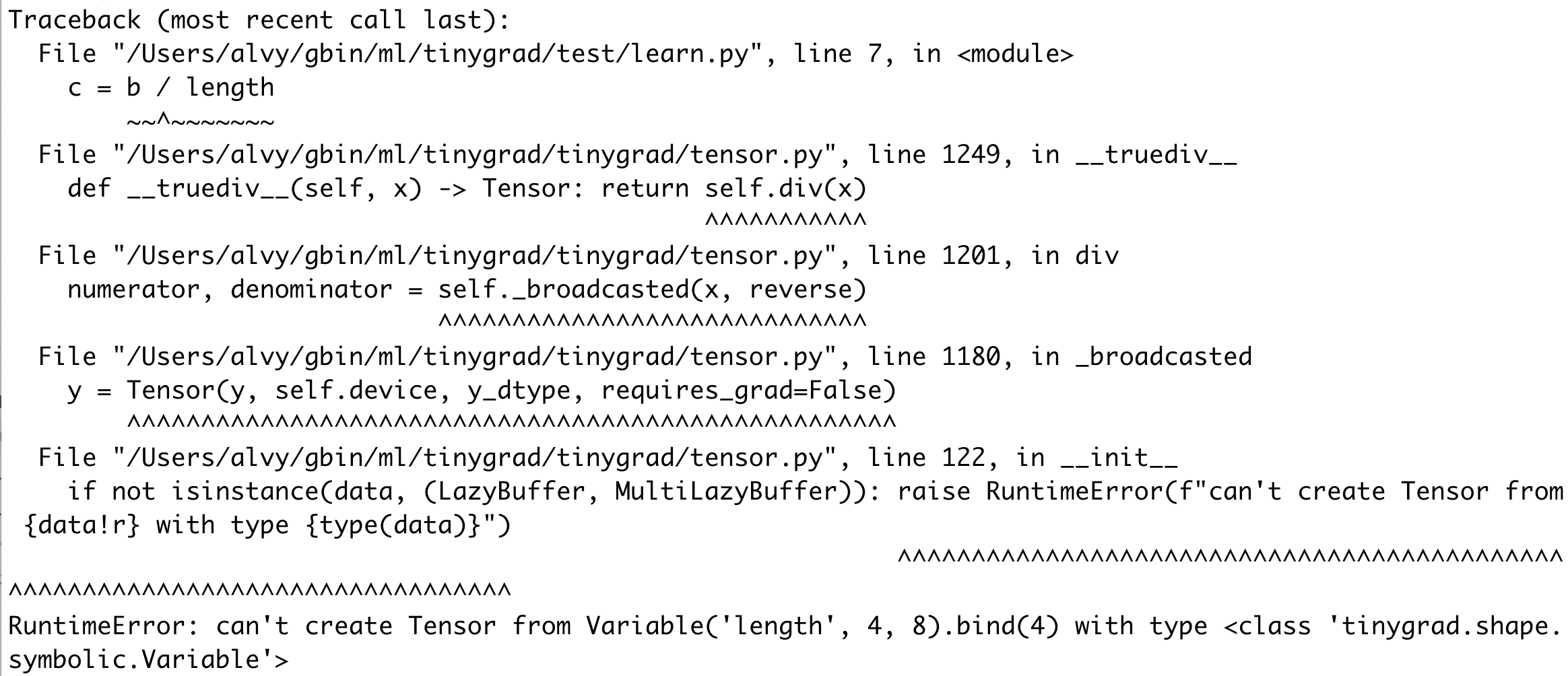

Now back to the bounty question, can we do the same for mean? You can

try this script and you will get an error (note that I am running

against commit id f3de17912f45cf7e45aa2004a0087346fd5fc54a) and

I used the div method directly to calculate the mean

because the mean() method has some asserts that prevent you from

trying this out at all:

from tinygrad import Tensor

from tinygrad.shape.symbolic import Variable

length = Variable('length', 4, 8)

length = length.bind(4)

a = Tensor.rand(length)

b = a.sum()

c = b.div(length)

print(c.numpy())

The error message says you can’t create a tensor using symbolic value. Tracing

the code, we see that the divison operator will attempt to create a tensor

for any non-tensor operand via the _broadcasted method:

class Tensor:

def div(self, x:Union[Tensor, ConstType], reverse=False, upcast=True) -> Tensor:

numerator, denominator = self._broadcasted(x, reverse)

if upcast: numerator, denominator = numerator.cast(least_upper_float(numerator.dtype)), denominator.cast(least_upper_float(denominator.dtype))

return F.Div.apply(numerator, denominator)

def _broadcasted(self, y:Union[Tensor, ConstType], reverse:bool=False, match_dtype:bool=True) -> Tuple[Tensor, Tensor]:

x: Tensor = self

if not isinstance(y, Tensor):

# make y a Tensor

# assert isinstance(y, (float, int, bool)), f"{type(y)=}, {y=}"

if isinstance(self.dtype, ImageDType) or dtypes.is_float(x.dtype) or (dtypes.is_int(x.dtype) and isinstance(y, int)): y_dtype = x.dtype

else: y_dtype = dtypes.from_py(y)

y = Tensor(y, self.device, y_dtype, requires_grad=False)

if match_dtype:

output_dtype = least_upper_dtype(x.dtype, y.dtype)

x, y = x.cast(output_dtype), y.cast(output_dtype)

if reverse: x, y = y, x

# broadcast

out_shape = broadcast_shape(x.shape, y.shape)

return x._broadcast_to(out_shape), y._broadcast_to(out_shape)

If you ponder about why sum works and mean doesn’t, it’s because summing

things up does not introduce new variables, it’s just adding the values

within itself. However, calculating the mean requires you to divide the sum

by a new value, and this new value has to be of type tensor. Similarly,

you can see that max and min also work, whereas std and var do not.

The goal of the bounty is now clear - allow Tensor to accept symbolic values.

Let’s look at where to get started, aka where the error was thrown, when you create a tensor, its initializer checks the data type:

if isinstance(data, LazyBuffer): assert dtype is None or dtype == data.dtype, "dtype doesn't match, and casting isn't supported"

# ...

if not isinstance(data, (LazyBuffer, MultiLazyBuffer)): raise RuntimeError(f"can't create Tensor from {data!r} with type {type(data)}")

if isinstance(device, tuple):

# TODO: what if it's a MultiLazyBuffer on other devices?

self.lazydata: Union[LazyBuffer, MultiLazyBuffer] = MultiLazyBuffer.from_sharded(data, device, None) if isinstance(data, LazyBuffer) else data

else:

self.lazydata = data if data.device == device else data.copy_to_device(device)

The starting point would be to make this initializer accept Variable and have

downstream operations to recognize this datatype.

Feel free to now take a look at the PR that implemented it and hopefully it become clear what it accomplished: https://github.com/tinygrad/tinygrad/pull/4362