tinygrad-notes

Introduction to the internals

There are two facades of tinygrad: the deep learning part, and the compiler part. The former concerns how weights are updated, how neurons are represented as tensors and matrix multiplication. This is better explained by Karpathy’s Youtube tutorial

The second part is the compiler, its main concern is how to generate GPU code for any given tensor computation and handle the relevant scheduling (i.e. “when and how to run those generated code”).

Let’s use a simple computation example, where we are adding two tensors element-wise:

from tinygrad import Tensor

a = Tensor.empty(4, 4)

b = Tensor.empty(4, 4)

print((a+b).tolist())

# [[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0], [0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0], [0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0], [0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]]

The result is unsurprisingly boring, just a nested list of zeros. But this small example illustrates a myriad of interesting details on the compiler aspect.

First, the computation is lazy, you have to call one of tolist(), numpy(), realize() on the tensor to get the result.

Try for yourself what happens if you omit the tolist invocation.

print(a+b)

<Tensor <UOp METAL (4, 4) float (<Ops.ADD: 44>, None)> on METAL with grad None>

Second, we can easily pry under the hood on how this computation occurred (despite being zeros, these zeros actually

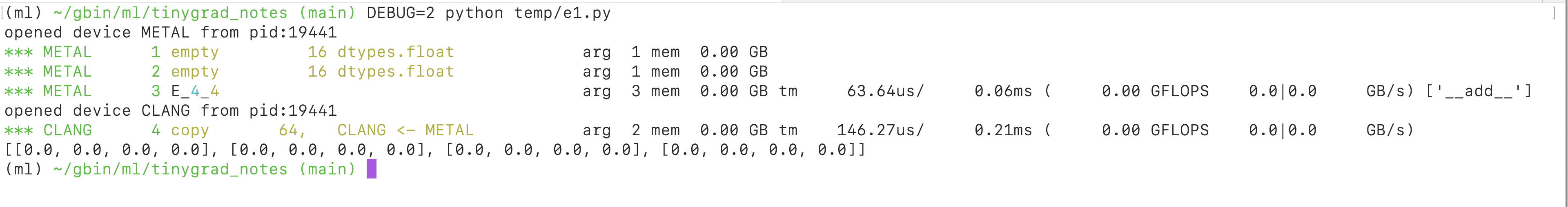

get added with each other!) Let’s run the script again with DEBUG=2 python script.py:

There are four main rows in the output. The first two (“empty”) refers to the variable a and b, which serve as the input to the addition. Their data is populated with zeros, and is designated with “empty”. Under the hood, this uses the default memory allocation method for the GPU device. If we want to put actual data in it, there would be a “transfer” method (not covered yet). The number 16 refers to the fact we allocated 16 elements, each of which is of dtype “float”. “float” is a shorthand for “float32”, occupying 4 bytes, or 32 bits (similarly, “double” is a shorthand for float64, occupying 64 bits, or 8 bytes). We see that the next part says 0.00GB, it’s just rounded down to zero, because our example is too small.

The third row designate the computation. “E” is short for “elementwise”, meaning the input and output have the same shape and we are doing elementwise operation. “_4_4” refers to the shape of such computation. The color also convey special meanings. This can get quite complicated, so I’ll gloss over the some details. Think of it this way, we have 16 elementwise operation, so the numbers must somehow add to 16. Depending on how things are optimized, you may see “E_16”, meaning we launched 16 unit of computation. You may see “E_4_4”, meaning we have launched 4 by 4 unit of computation. This could mean a few things, depending on how the two 4s are colored. It could be that we have 4 blocks, each block containing 4 threads (CUDA parlance). It could be that we have 4 blocks, and each block handles 4 elements. I might write a separate post explaining the meanings of these colors (they are already documented in the source code though).

We see some more useful info on this line as well. “arg 3” means we have three arguments. GPU function don’t return anything, instead they modify the input. Since we are adding two tensors, and storing the result, we have to pass all three as arguments. “mem 0.00 GB”, this refers to how much memory was used, again it’s just rounded down. “tm 25.88 us / 0.03ms”, this says our computation/kernel took 25 micro seconds, and the total elapsed time since start of program is now at 0.03 milliseconds. We also see the output for the computation speed measured in GFLOPS, and the memory throughput measured in “GB/s”. These give handy insights into how our kernel is performing.

The last row corresponds to “tolist()”. Recall that data on GPU are not directly accessible, we have to copy them back to CPU for printing and illustration. So here we are copying them from the GPU (METAL) to CPU (CLANG).

Next let’s run the script again with more debug info, DEBUG=4 python script.py, and among the output, look for some

C++ looking code:

#include <metal_stdlib>

using namespace metal;

kernel void E_4_4(device float* data0, device float* data1, device float* data2, uint3 gid [[threadgroup_position_in_grid]], uint3 lid [[thread_position_in_threadgroup]]) {

int lidx0 = lid.x; /* 4 */

int alu0 = (lidx0<<2);

float4 val0 = *((device float4*)((data1+alu0)));

float4 val1 = *((device float4*)((data2+alu0)));

*((device float4*)((data0+alu0))) = float4((val0.x+val1.x),(val0.y+val1.y),(val0.z+val1.z),(val0.w+val1.w));

}

This is the generated GPU code for apple’s platform. Let me also show the version for CUDA:

#define INFINITY (__int_as_float(0x7f800000))

#define NAN (__int_as_float(0x7fffffff))

extern "C" __global__ void __launch_bounds__(4) E_4_4(float* data0, float* data1, float* data2) {

int lidx0 = threadIdx.x; /* 4 */

int alu0 = (lidx0<<2);

float4 val0 = *((float4*)((data1+alu0)));

float4 val1 = *((float4*)((data2+alu0)));

*((float4*)((data0+alu0))) = make_float4((val0.x+val1.x),(val0.y+val1.y),(val0.z+val1.z),(val0.w+val1.w));

}

Make sure you understand what this code is doing before proceeding. Tinygrad is concerned about how to generate such GPU code, so a lot of complexity lies in the “how”, rather than explaining “what” this code is doing. You can think of tinygrad as a high level tool to save you from hand writing all the C++ code. Feel free to read up on CUDA tutorials.

The code we see is somewhat optimized, because we are launching only 4 threads, instead of 16, and allowing each thread

to take advantage of vectorized data. We can also see the unoptimized version, by passing a NOOPT flag:

DEBUG=4 NOOPT=1 python script.py:

Apple’s Metal:

#include <metal_stdlib>

using namespace metal;

kernel void E_16(device float* data0, device float* data1, device float* data2, uint3 gid [[threadgroup_position_in_grid]], uint3 lid [[thread_position_in_threadgroup]]) {

int gidx0 = gid.x; /* 16 */

float val0 = *(data1+gidx0);

float val1 = *(data2+gidx0);

*(data0+gidx0) = (val0+val1);

}

CUDA:

#define INFINITY (__int_as_float(0x7f800000))

#define NAN (__int_as_float(0x7fffffff))

extern "C" __global__ void __launch_bounds__(1) E_16(float* data0, float* data1, float* data2) {

int gidx0 = blockIdx.x; /* 16 */

float val0 = *(data1+gidx0);

float val1 = *(data2+gidx0);

*(data0+gidx0) = (val0+val1);

}

Run a few more examples yourself!

print((a*b).tolist())

print((a.sum(0).tolist()))

Understanding the Intermediate Representation

Like any other compiler, tinygrad uses an Abstract Syntax Tree to represent the computation before generating the

code. It is called UOp:

class UOp:

op: Ops

dtype: dtypes

src: tuple(UOp)

arg: None

The op field is the operation for this node, examples are Ops.ADD, Ops.SUM, Ops.EMPTY, etc. The

dtype field is the data type, like dtypes.float. The src field represents the parents of this node. For example, our ADD would have the two nodes

it derived from. The arg field is set to None for our addition,

but suppose we are doing a sum, then we might want to specify which dimension we are summing, that’s where the dim

integer would go.

UOp(Ops.ADD, dtypes.float, arg=None, src=(

UOp(Ops.EMPTY, dtypes.float),

UOp(Ops.EMPTY, dtypes.float)

))

Such UOp can take on multiple forms, depending on the context, and it can get a bit confusing. The general strategy

to understand it is that they are generated when we want to “realize” a tensor (tolist()). Each UOp tree represent

a complete kernel. Upon generation it describes things on a high level, like what I have just shown. It then gets

progressively “lowered” into a form that can be used for actual code generation.

Code generation

The UOp used for code generation contains much more details and is of lower level. Here I have built an example that you can use to play around. If things go out of date, commit id is: ae00fa3b2833dbe0595d54d5fb0b679e1731ae01

Suppose we just want to add two numbers:

from tinygrad.renderer.cstyle import MetalRenderer

from tinygrad.uop.ops import UOp, Ops

from tinygrad import dtypes

const = UOp(Ops.CONST, dtypes.float, arg=1.0)

add = UOp(Ops.ADD, dtypes.float, src=(const, const), arg=None)

print(add)

print(MetalRenderer().render([

const,

add

]))

The add variable shows something like:

UOp(Ops.ADD, dtypes.float, arg=None, src=(

x0:=UOp(Ops.CONST, dtypes.float, arg=1.0, src=()),

x0,))

The walrus (:=) operator just make the output less verbose, indicating the two “const” are the same instance. And

let’s see the rendered code:

#include <metal_stdlib>

using namespace metal;

kernel void test(uint3 gid [[threadgroup_position_in_grid]], uint3 lid [[thread_position_in_threadgroup]]) {

float alu0 = (1.0f+1.0f);

}

Let me show you the CUDA version also, where you would replace the import:

from tinygrad.renderer.cstyle import CUDARenderer

from tinygrad.uop.ops import UOp, Ops

from tinygrad import dtypes

const = UOp(Ops.CONST, dtypes.float, arg=1.0)

add = UOp(Ops.ADD, dtypes.float, src=(const, const), arg=None)

print(add)

print(CUDARenderer("sm_50").render([

const,

add

]))

Note that you have to pass in the “architecture” as argument, it affects the compiler, this value is set automatically

by querying cuDeviceComputeCapability, for our render purpose, pass in just two digits would work.

#define INFINITY (__int_as_float(0x7f800000))

#define NAN (__int_as_float(0x7fffffff))

extern "C" __global__ void __launch_bounds__(1) test() {

float alu0 = (1.0f+1.0f);

}

So the result isn’t that interesting, in fact, this kernel wouldn’t ever be rendered in a real example, because adding two constants is “folded” before the render stage, so you get the value 2, instead of calculating it. This is one of the optimization techniques. Let’s see another example that renders the thread position:

print(MetalRenderer().render([

UOp(Ops.SPECIAL, dtypes.int, arg=("gidx0", 16))

]))

#include <metal_stdlib>

using namespace metal;

kernel void test(uint3 gid [[threadgroup_position_in_grid]], uint3 lid [[thread_position_in_threadgroup]]) {

int gidx0 = gid.x; /* 16 */

}

On CUDA:

#define INFINITY (__int_as_float(0x7f800000))

#define NAN (__int_as_float(0x7fffffff))

extern "C" __global__ void __launch_bounds__(1) example() {

int gidx0 = blockIdx.x; /* 16 */

}

The index op (SPECIAL) is used for specifying the position of a kernel within its launch grids. The renderer will

also handle the count, so it renders .x .y automtically if you pass more than 1:

print(CUDARenderer("sm_50").render([

UOp(Ops.SPECIAL, dtypes.int, arg=("gidx0", 16)),

UOp(Ops.SPECIAL, dtypes.int, arg=("gidx1", 16))

]))

extern "C" __global__ void __launch_bounds__(1) test() {

int gidx0 = blockIdx.x; /* 16 */

int gidx1 = blockIdx.y; /* 16 */

}

See my posts on pattern matcher for how this renderer engine works internally, at the end you get to see the UOp for this kernel:

#include <metal_stdlib>

using namespace metal;

kernel void rendered(device float* data0, uint3 gid [[threadgroup_position_in_grid]], uint3 lid [[thread_position_in_threadgroup]]) {

int gidx0 = gid.x; /* 16 */

*(data0+gidx0) = (0.5f+0.5f);

}

Make sure you have a good understanding of all the UOps involved in this kernel!

Where to go next

Let me summarize what we have so far. We look at the tinygrad internals from the compiler perspective, mainly concerning

its ability to render GPU code. This rendering process is handled by a “pattern matcher”, that progressively turn the

UOp recursive structure into C++ code. All the tensor operation is lazy, meaning they only get evaluated when one of

tolist(), numpy(0) or realize is called. When calling these operation, the operation represented by the tensor

is converted into a high level UOp, like the first one we saw where we are adding two Ops.EMPTY. This high level

UOp is then lowered into a form that can be consumed by the renderer.

I didn’t yet cover how the conversion from tensor to high level UOp happens. This is referred to as “scheduling”, because each UOp represent a kernel, that’s also where kernel fusion happens.

One fundamental idea in tinygrad is that almost everything can be represented by simple elementwise and reduce operations, combined with zero-cost shape movement. So for the next part make sure you understand how shapetracker works, together with how matmul and conv are implemented.